Population and community responses to temperature

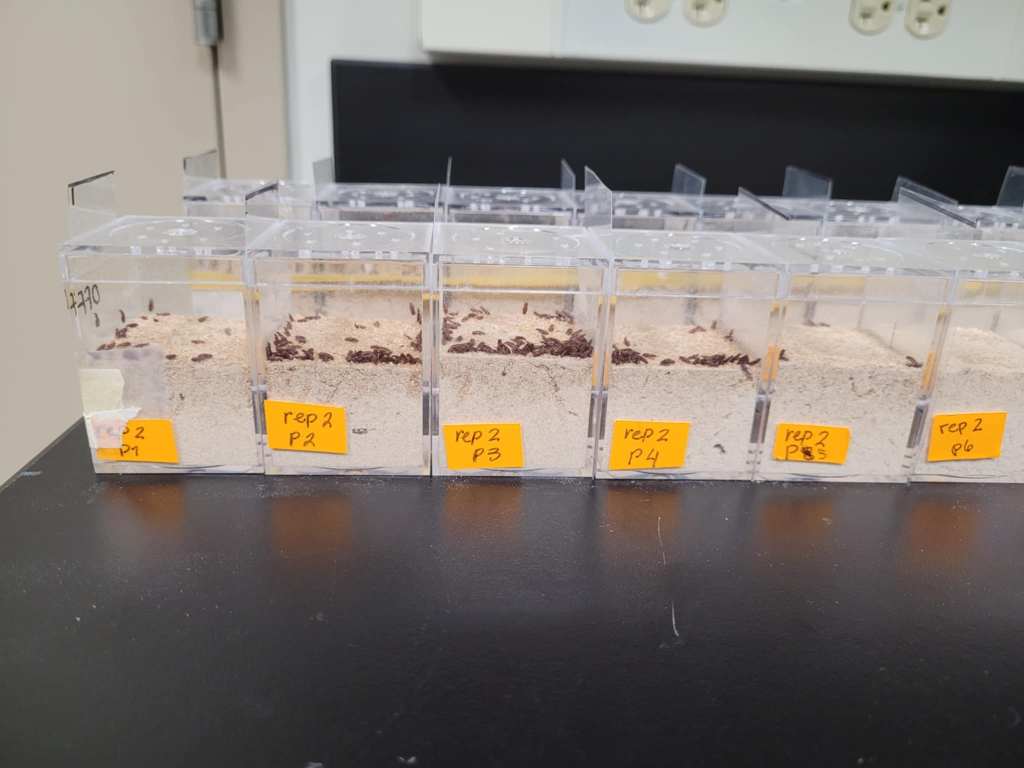

Global temperatures are rising as a result of human activities, and one of the main aims of the lab is to uncover general rules for how populations and communities respond to temperature that can help us predict how the natural world will change as it warms. We test theory about the effects of temperature on a range of population and community responses. We use experiments in the lab and field to answer questions like:

How does temperature affect the coexistence of competing species?

How do heat waves affect long-term population dynamics?

Does temperature change the importance of arrival order at a site?

Eco-evolutionary responses to global change

Due to the ongoing impact of humans on the natural world, ecological communities are increasingly faced with new and shifting environmental conditions. Species can respond to these global changes ecologically, for example by altering when they emerge or reproduce, or evolutionarily, by adapting to new conditions. We’re interested in understanding the interactions between species’ ecological and evolutionary responses to global change, especially temperature change. We use experimental evolution and data synthesis to answer questions like:

How does adaptation to different temperatures affect competitive ability?

Are there general trends across taxa in how life history traits evolve in response to climate change?

How does temperature affect species’ ability to rapidly adapt to deteriorating environmental conditions?

Dispersal and diversity in patchy landscapes

Many species rely on patchily distributed resources such as ponds or host plants, and dispersal between these habitat patches can promote the diversity of the species that inhabit them. We’re interested in understanding how local within-patch dynamics and dispersal jointly drive population and community dynamics, and how global changes such as warming and habitat fragmentation are changing this. We’re also increasingly interested in experimentally testing the factors that drive dispersal in the context of range expansion. We use lab and field experiments to address questions like:

How does temperature affect the rate of dispersal and range expansion?

What are the combined effects of temperature and predation on dispersal behaviour?

How does warming alter the effect of habitat connectivity on biodiversity?

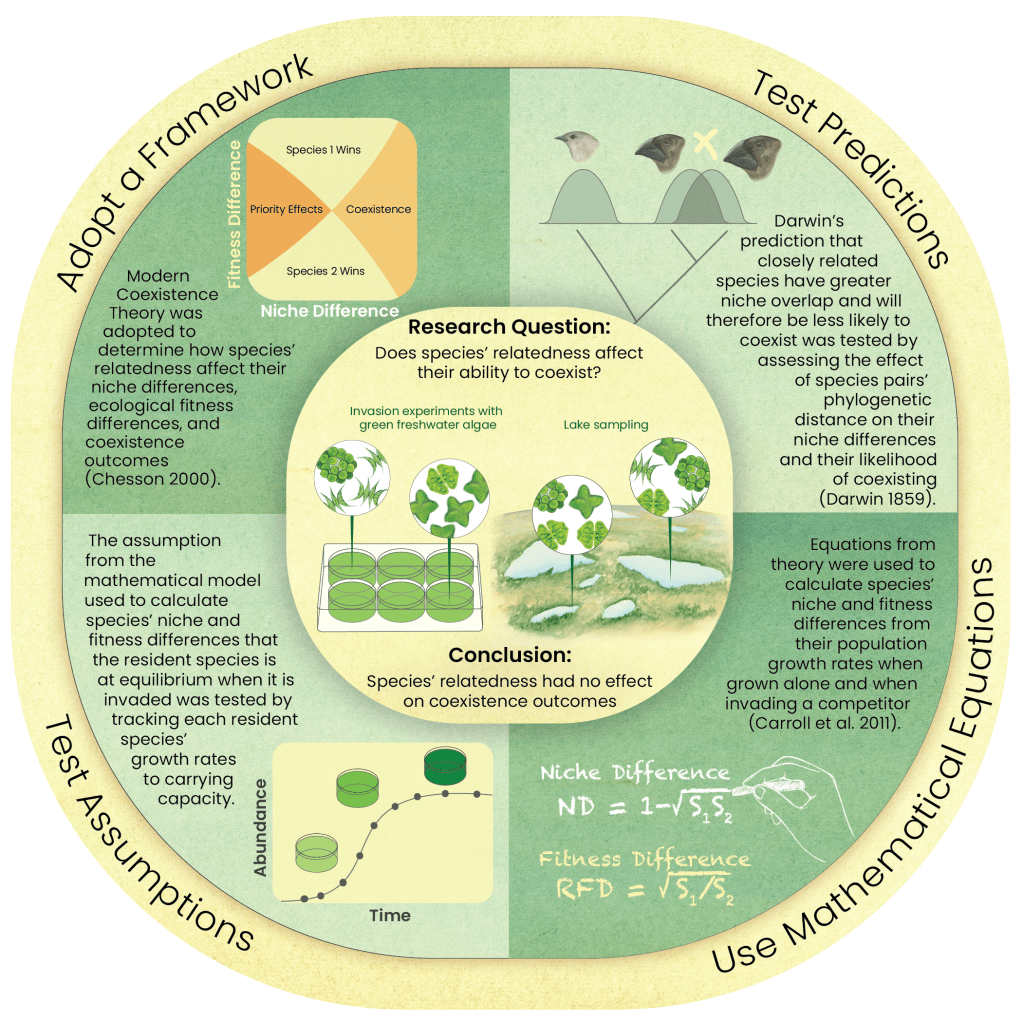

Connecting theory with empirical research

Although the benefits of strong links between theoretical and empirical research are widely acknowledged by scientists, there are often gaps between theory and experiments in scientific research, and the field of ecology is no exception. An underlying theme in all of our research is strengthening connections between theory and empirical research. We also explicitly tackle questions like:

What can empiricists do to better understand and use theory?

How can we better integrate the common theoretical assumption of equilibrium into empirical tests?

How can theoriticians make their work more accessible?